The savagery of the senior Nazis is infamous. So what possessed any woman to wed such men and bear their children? In this series from James Wyllie’s chilling book, we reveal the women behind Hitler’s henchmen — and, in the first instalment, we look at the Fuhrer’s own notorious First Lady Eva Braun…

Hitler gave his private secretary a task in 1930 that required secrecy and discretion — checking out the ancestry of a 17-year-old girl he had met at a photographic studio in Munich, where she was working as an assistant.

Was she from good Aryan stock? After completing a thorough investigation, Martin Bormann was able to confirm that Eva Braun did not possess a single drop of Jewish blood.

From then on, Hitler regularly dropped in on her at the studio, taking her out to dinner or a film.

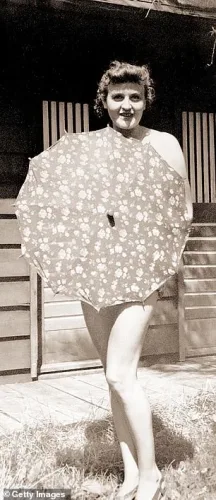

He probably started sleeping with her in early 1932. In some respects, Eva didn’t fit the mould of Nazi womanhood: she smoked, followed the latest American dance crazes, read fashion magazines and wore make-up.

Yet in other ways, she embodied Hitler’s ideal: she was athletic and sporty, a true blonde and had almost no interest in politics.

Best of all, she was emotionally immature and easy to manipulate.

After allowing Hitler to seduce her, however, Eva became distraught, imagining herself abandoned because she hardly ever saw him.

One day, in despair, she scribbled a farewell note and shot herself.

The bullet lodged in her neck, just missing the artery. Bleeding profusely, she managed to call a doctor, who had her carted off to hospital. Hitler was shocked, vowing to see her more often. And he did for a few years.

Then, in 1935, for weeks on end, he failed to call. When Eva finally got to see him for two hours, he returned to Berlin

without saying goodbye.

For the next two months, her moods fluctuated wildly, reaching a near-hysterical peak that May — when she took an overdose of sleeping pills. Her younger sister found her in time.

At this point, Hitler realised it was time to bring Eva out into the open

In some respects, Eva didn’t fit the mould of Nazi womanhood: she smoked, followed the latest American dance crazes, read fashion magazines and wore make-up

Taking her to the Nazi party rally in Nuremberg, he introduced her to the far brighter Magda Goebbels.

The wife of the Nazis’ propaganda chief was ‘completely shocked’ by ‘this capricious and dissatisfied-looking girl sitting on the VIP rostrum’.

When some of Magda’s negative remarks got back to Hitler, he was so furious that he refused to see her for more than six months.

In 1936, he moved Eva to the Berghof, his Alpine retreat near Berchtesgaden. But he didn’t want his girlfriend around when he was receiving VIPs or foreign statesmen. On a regular basis, she was banished to her room, or back to her Munich villa, or told to disappear for a few hours.

Yet it was largely down to Eva’s quiet influence that Joseph and Magda Goebbels were never encouraged to have a property in the area.

One day, Magda — then heavily pregnant — asked Eva if she wouldn’t mind tying her shoelace as she found it difficult to bend over. Eva calmly rang a bell and got her maid to do it.

Life at the Berghof was staid. Most days, Hitler and Eva would have tea and cake at 4pm and he would sometimes fall asleep in his chair.

Most evenings culminated in either the screening of a movie or one of Hitler’s endless monologues, through which his audience struggled to stay awake.

After allowing Hitler to seduce her, however, Eva became distraught, imagining herself abandoned because she hardly ever saw him. One day, in despair, she scribbled a farewell note and shot herself. Pictured: Eva Braun and Adolf Hitler, with their two dogs Wulf and Blondi, in 1942

Eva began to assert herself more during the war years. When the Nazis banned cosmetics, she made sure she was exempted. She also insisted on sanitary towels when ordinary women had to come up with home-made alternatives.

The rationing of clothing had no impact on her, either. Eva continued to wear three new dresses a day — one for lunch, one for tea and one for dinner — many from French and Italian fashion houses.

When it became clear that Germany was losing the war, she insisted on joining Hitler at his bunker in Berlin.

‘I have come because I owe the Boss for everything wonderful in my life,’ she told his secretary.

The atmosphere at Hitler’s birthday party on April 20, 1945, was more downbeat than usual.

That morning, Soviet artillery had started shelling the city centre.

Hitler retired early to bed. Eva, however, was determined to have some fun. According to one of Hitler’s young secretaries, ‘a restless fire burned in her eyes’; Eva wanted ‘to dance, to drink, to forget’. Sweeping up Martin Bormann and a few others, she cracked open some champagne and played one record over and over again, wartime hit Blood Red Roses Speak Of Happiness To You.

Adolf Hitler with guests at at his residence, the Berghof, in 1939. Front row left to right: Wilhelm Bruckner (Hitler’s Chief Adjudant), Christa Schroder (Hitler’s secretary), Eva Braun, Adolf Hitler, Gretl Braun (Eva’s sister), Adolf Wagner (Gauleiter of Munich) and Otto Dietrich (press chief)

On April 29 Eva and Hitler became husband and wife. In the hours before the wedding, Hitler had written in his last will and testament: ‘I have now, before ending this earthly existence, decided to take as my wife the girl who, after years of loyal friendship, has voluntarily returned to the almost besieged city to share her fate with mine. It is her wish to join me in death as my wife.’

At the ceremony, which was attended by Bormann and the Goebbels, Eva wore a silk taffeta dress and her finest jewellery.

Although the bunker was being rocked by shellfire, the mood was ‘festive’, according to Hitler’s chauffeur. There was champagne and sandwiches, and they all ‘reflected with nostalgia on the past’.

The next day, at 3.15pm, Hitler and Eva retreated into their shared quarters. His valet and Bormann waited outside the door for a while before entering.

When Bormann saw the two corpses on the sofa, he ‘turned white as chalk’. Hitler had taken poison — hydrogen cyanide — then shot himself in the temple with his 7.65mm pistol, which lay on the floor near his feet. Eva, dressed in black, was slumped next to him. According to the valet, the poison had left its mark, contorting her pretty face. She was 33.

A fanatical Nazi, Hess was deputy Fuhrer to Hitler from 1933 to 1941. He gave the Christmas radio address every year, spoke at numerous fascist rallies and signed into law the legislation that stripped all German Jews of their rights.

Aged 20, Ilse Prohl was living in a Munich student hostel when she ran into a fellow lodger. He was wearing a tattered uniform and she was struck by his gaunt appearance: thick eyebrows that almost met in the middle, sunken eyes and a haunted expression.

The man introduced himself as Rudolf Hess. For Ilse, a doctor’s daughter, it was an instant attraction — though, as she was later to discover, the virginal Hess had no interest in sex.

Aged 20, Ilse Prohl was living in a Munich student hostel when she ran into a fellow lodger. The man introduced himself as Rudolf Hess. Pictured: Ilse and Rudolf Hess (second and third from left) at the 1936 Berlin Olympics

Lacking a physical dimension, their relationship owed much to their shared admiration for Hitler. Here was the man, they thought back in 1920, who was destined to set Germany on the road to glory.

Hess, a 26-year-old World War I veteran, was soon involved in the frequent brawls between Nazi supporters and their Left-wing opponents, while Ilse spent most of her spare time delivering Nazi leaflets, putting up posters and helping out with the party newspaper. Their reward was spending time with their hero.

Ilse later described how Hitler enjoyed doing impressions and liked nothing better than listening to a well-told funny story — as long as it wasn’t about him.

A measure of how much he trusted her is that she helped edit his book, Mein Kampf, while Hess became his secretary and one of the few men who could see Hitler whenever he wished.

After seven sexless years, however, Ilse began losing patience with her boyfriend. It was Hitler who settled the matter while the three of them were in a cafe.

Taking her hand, he placed it in Hess’s and asked her if she’d ‘ever thought about marrying this man?’. Unable to deny Hitler’s wishes, Hess stopped procrastinating and married Ilse in 1927.

Not that her sex life appeared to improve much after that. She complained to a friend that she ‘felt like a convent girl’.

The Hesses settled in a modest villa, taking regular hiking and skiing holidays. They liked to think of themselves as art patrons, and collected Expressionist paintings by Georg Schrimpf, later denounced by the Nazis as degenerate art.

When Hitler — who had always hated Schrimpf’s work — visited Ilse and her husband in 1934, he was disturbed to see such ‘abominations’ on their walls.

Up to that point, Hess had seemed the logical choice to succeed the Fuhrer; he was now head of the party and had been at the Nazi leader’s side for more than a decade.

But after that evening, Hitler changed his mind, telling his press secretary that he could not possibly allow somebody with ‘such a lack of feeling for art and culture’ to be his second-in- command. Hitler wasn’t the only prominent Nazi who found fault with the Hesses.

Magda, the wife of propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels, claimed that ‘parties at the Hess home’ were ‘so boring that most people refused invitations’. Nobody was allowed to smoke, no alcohol was served and ‘the conversation was as thin and dull as the drinks’.

Hess worked hard to overcome his aversion to sex, and eventually started taking a hormone-based potion to boost his virility. Their efforts were rewarded: Ilse became pregnant in 1937. Pictured: Ilse Hess with son Wolf

Ilse did her best to compensate for her husband’s reluctance to have fun but it was an uphill struggle. When the film director Leni Riefenstahl dropped by for tea, for instance, Hess just sat there, not uttering a word.

Still, although the couple were mocked by leading Nazis, their fanaticism never waned.

Every year, Ilse sat in the front rows on the podium during the Nuremberg party rally, a week-long homage to Hitler that grew more extravagant with every passing year. Neither she nor her husband — both committed anti-Semites — raised any objections to the concentration camps.

Yet somehow, Ilse rubbed Hitler up the wrong way. Privately, he frequently criticised ‘her ambition’ and complained that she tried ‘to dominate men and therefore almost [lost] her own femininity’.

He thought it was wrong for women to have political opinions, and if they did, they should keep their mouths shut.

Although a vegetarian himself, he was also irritated when Ilse and Hess followed suit.

When Hitler invited Hess to lunch, he brought along his own lunchbox, explaining that ‘his meals had to be of a special bio-dynamic origin’. Hitler suggested that he eat at home in future, and rarely invited him out again.

Meanwhile, the Hesses were growing increasingly distressed at their inability to have a child. Given their self-image as the torch-bearers of the Nazi movement, it felt shameful not to have added one of their own to the ranks. Hess worked hard to overcome his aversion to sex, and eventually started taking a hormone-based potion to boost his virility.

Their efforts were rewarded: Ilse became pregnant in 1937. Eager for a boy, Hess searched for favourable omens by trapping wasps in honey jars and then counting them. According to folklore, if a larger than average number of wasps appeared during the summer, you could expect a higher percentage of male births.

Wolf, their only child, was born that year. According to the Goebbels, Hess ‘danced with joy’ in a manner that resembled ‘South American Indians’. He then issued an order to all the regional party bosses to send ‘bags of German soil’ to ‘spread under a specially built cradle’ so that his son could begin life ‘symbolically’ on soil from every corner of the Fatherland.

There is some evidence that Eva persuaded Hitler not to have Ilse arrested, and to give her a monthly pension. None of which stopped Hess’s wife from becoming a pariah with an uncertain future. Pictured: Ilse in a Messerschmidt Cabin Scooter with Wolf

Goebbels found the request highly amusing, and dispatched a sealed package of manure from his garden.

Four years later, Ilse noticed her husband was unusually tense. She was convinced he was planning something secretly. He was. On May 10, 1941, the couple had tea at 2.30pm. Before leaving, she recalled, ‘he kissed my hand and stood at the door of the nursery, grown suddenly very grave, with the air of one in deep thought’.

Unknown to her, he then climbed into a plane and flew himself to Scotland on a solo mission to bring about peace between Britain and Germany. He appears to have been fired up by a brief meeting at the Olympic Games with the Duke of Hamilton — who was in favour of peace on German terms.

What Hess hoped to do was persuade the British to abandon the war — thus leaving Hitler free to concentrate on conquering Russia.

Ilse started to worry when he didn’t return home that night: ‘The next two days, we knew absolutely nothing of what had happened.’ She would not see her husband again for 28 years. Hitler reacted to her husband’s escapade with fury and incomprehension. He immediately had all of Hess’s private staff arrested, some of whom languished in camps until 1944.

As for Ilse, she was given a thorough grilling by his private secretary Martin Bormann, who then asked her to list which items in the Hess flat belonged to the state and which belonged to her. It turned out that only the carpets were hers, while everything else was government property.

One of her few supporters was Hitler’s girlfriend, Eva Braun, who told Ilse: ‘I like you and your husband best of all. Please tell me if things become unbearable, because I can speak to the Fuhrer without Bormann knowing anything about it.’

In July 1947, Hess was transferred to Spandau prison in Berlin. Pictured: Ilse leaves Spandau prison after visiting her husband. She is accompanied by her son Wolf and his wife

There is some evidence that Eva persuaded Hitler not to have Ilse arrested, and to give her a monthly pension. None of which stopped Hess’s wife from becoming a pariah with an uncertain future.

Hess discovered that the British government had no intention of coming to terms with Hitler. They locked up the deputy Fuhrer for the rest of the war. He twice attempted to kill himself — once by dropping 25 ft from a landing and once by cutting his chest with a bread knife.

After some months, Hitler agreed to let Ilse write to Hess — letters that took eight months to arrive. In one reply, her husband said he was ‘happy to see’ that she remained loyal to the Fuhrer.

A few weeks after the war ended, he wrote to his wife that the time they had shared with Hitler had been ‘full of the most wonderful human experiences’ and it had been a privilege to have participated ‘from the very beginning in the growth of a unique personality’.

In October 1945 he was transferred to Nuremberg, put on trial at the International Military Tribunal and sentenced to life imprisonment. In the dock, he cut a bizarre figure, reading novels, muttering to himself and sleeping, while in his cell he threw violent tantrums. Offered the chance to see his wife, he refused.

In July 1947, he was transferred to Spandau prison in Berlin. He and Ilse continued to correspond. By 1955, she’d opened a guesthouse high in the Bavarian Alps, with a room reserved for her husband’s return. She campaigned for the rest of her life for his release.

In 1957, Hess again tried to kill himself — this time by slashing his wrists with a piece of glass. Then, 12 years later, he came close to death with a perforated ulcer.

At that point, he finally asked to see Ilse and Wolf again. They weren’t allowed to touch and Wolf could tell his mother was ‘on the edge of tears’.

After Hess recovered, Britain, France and the U.S. agreed it was time to release him. The Soviets refused. His so-called peace mission, they said, had been undertaken only to make it easier for Hitler to crush the Soviet Union.

They also pointed out that he remained an unreconstructed Nazi, whose writings in prison were both anti-Semitic and full of contempt for liberal democracy. But they agreed he could receive one visitor a month.

In 1977, Hess tried to sever an artery with a knife. Ilse saw him for the last time in October 1981, by which time he had pleurisy and a dodgy heart. Wolf continued with candlelit vigils outside Spandau. But in the end, Hess took matters into his own hands: in 1987, at the age of 93, he hanged himself with an extension cable.

Ilse died in a nursing home in 1995 aged 95. Through everything, she had held on to her warped principles.