-By Abdul Mahmud

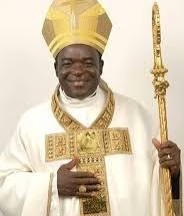

Most Reverend Matthew Kukah has spoken again. This time, he tells Nigerians that the country is not experiencing a Christian genocide. He cites numbers, he questions sources, and he dismisses claims of persecution. He reminds us that genocide is defined by intent, not by pools of blood and burnt out churches. The bishop speaks as if death can be measured only by some theological precision. He speaks as if suffering requires validation from the Vatican. He speaks as if the cries of widows, orphans, and Christian communities terrorised across northern Nigeria are hearsay unless confirmed by his office. Bishop Kukah has carved a niche for himself in Nigerian public life. Once, he poked the eyes of oppressors with fearless sermons and daring speeches. He once seemed a gadfly to power. He once understood the language of moral outrage. Today, he prefers the language of caution. Today, he interprets atrocities for two conveniences: those in charge of the nation-state and the convenience of his new theology. He does not question. He reduces horrors to mere numbers, questioning whether they can even be called horrors without an explicit intent behind them. He argues, with calculated sophistry, that genocide exists only when intent can be proven.

Let us examine his reductionism.

Kukah insists that unless a death can be tied to explicit intent to destroy Christians as a group, genocide cannot exist. He reduces complex realities into legalistic formulas. He discounts decades of chronic violence. He ignores the systematic targeting of communities based on faith. He dismisses eyewitness testimony as anecdotal. He scorns journalistic accounts as unverified. He trusts only his own calculations or those sanctioned by the Vatican. He elevates protocol over pain. He hides behind definitions while lives are extinguished, clergy men taken away or killed. Just yesterday Sunday (November 30-2025), the Cherubim and Seraphim Church in Ejiba, Yagba West Local Government Area of Kogi State was attacked. The pastor, wife and worshippers were abducted. Last week, Venerable Dachi was killed by his abductors – yes, in Bishop Kukah’s home state of Kaduna. Yet, he insists that genocide exists only when intent to destroy a group can be proven. This is a dangerous simplification. The international legal definition, as contained in the 1948 Genocide Convention, does indeed mention intent, but intent is not the sole criterion. Genocide encompasses acts committed with the knowledge that they will destroy, in whole or in part, a group. Systematic killings, forced displacement, destruction of homes, religious sites, and cultural institutions all count. One does not need a signed decree from the oppressor to establish genocide. The logic of intent alone ignores the lived reality of victims. Villages emptied of life, churches torched, children orphaned, communities terrorised – these are visible consequences. To demand proof of a private mental decision by the perpetrator before naming genocide is to demand the impossible. It is to turn suffering into speculation.

Scholars such as Raphael Lemkin, the man who coined the term genocide, emphasised that genocide is a process, a series of actions aimed at annihilating a group. Lemkin spoke of destruction through systematic oppression, not only through explicit declarations of intent. Legal scholars have expanded this understanding to include acts that produce predictable, devastating outcomes for targeted groups. Intent is important, but intent is not an escape hatch for those who reduce horror to definitions convenient to power. When Kukah speaks as though genocide can only exist with direct intent, he removes agency from the perpetrators while dismissing the lived experiences of the victims. He creates a loophole where terror, displacement, and massacres are rendered morally neutral because the legalistic proof of intent is hard to extract. This is not scholarship. It is a moral abdication. It is an evasion of responsibility. It is the language of those who interpret the sufferings of the many for the convenience of a few.

Genocide is not a theological abstraction. It is a social and human reality. It is measured in homes destroyed, lives cut short, and communities erased. It is seen in the fear that spreads across a region when faith alone becomes the marker for death. And no amount of definition by intent can erase these facts. Reducing genocide to intent alone is to argue that mass death is meaningless unless sanctioned by the conscious declaration of the killer. It is to ignore the predictable cruelty embedded in systemic attacks on a group. It is to allow killers to operate under a cloak of invisibility while the world debates whether the numbers and patterns satisfy a technical definition. This is why Kukah’s insistence is not merely wrong. It is dangerous. It is a subtle way to obscure reality and grant impunity. It is an intellectual exercise that leaves victims behind. By anchoring genocide to intent alone, Kukah dismisses history, legal scholarship, and moral obligation. He overlooks the fact that intent can be inferred from patterns of systematic harm. He ignores that international tribunals regularly rely on the consequences of acts to establish genocidal intent. He closes his eyes to the evidence that is in plain sight. He reduces horror to a debate about whether someone, somewhere, consciously decided to destroy Christians. He renders fire and blood secondary to paperwork and memos. In doing so, he betrays not only history but the very communities he claims to serve.

Though Kukah’s transformation from gadfly to the powerful into a defender of obsequious authority seems complete, it is only fitting to contrast him with priests of his kind who stood for truth to the very end. Enter Father Oscar Romero who stood in the pulpit while soldiers murdered the poor outside his window. He did not wait for permission. He did not demand audited statistics. He called out the machinery of terror. He mentioned the names of the dead. He counted their tears, their homes, their broken families. He did not hide behind definitions of intent. He recognised that injustice is self-evident. He acted because silence was complicity. He paid with his life. Contrast Kukah with Paulo Freire, the author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Freire understood that education is liberation. He knew that suffering must be named before it can be confronted. He rejected reductionist reasoning that blunted the edge of oppression. He demanded dialogue with the oppressed. He demanded the courage to see power as it functions. He understood that the world is not a ledger of intent. It is a battlefield where the powerful impose structural violence on the weak.

Also, contrast Kukah with South American priests who fought on the side of the poor. They did not measure genocide in intent. They counted what was visible. They confronted killers, militias, and corrupt governments. They challenged impunity. They refused to normalise cruelty. They understood that faith demands solidarity with victims. They embodied that courage that does not calculate permission before speaking truth. They knew that silence is a language that the oppressors understand well.

Kukah’s words on the floor of the Knights of St. Mulumba echo as reductionism. Pure and simple. He cites 1,200 burnt churches every year and asks rhetorically, “In which Nigeria?”. He questions why nobody asked the Catholic Church. He refuses to accept reports from victims, journalists, human rights organisations, or even other Christians. He elevates his own office as the sole arbiter of truth. He reduces genocide to intent alone as if fire, blood, and terror cannot speak for themselves. One wonders how he reconciles his words with his vocation. How does one preach the gospel of love and yet sanitises terror with numbers and legalistic definitions? How does one counsel peace while dismissing sufferings? How does one command moral authority while parroting the language of the oppressors? Once, Kukah feared the powerful. He was our much-sought after and regular speaker at the Church and Human Rights Workshops of the Civil Liberties Organisation in the early 1990s at Ijebu-Ode and elsewhere. Now, he comforts power and the abusers of the right to life. Once, he demanded accountability. Now, he reframes accountability as optional. Once, he was the gadfly. Today, he is the evangelist of the oppressors.

Nigeria does not need semantics.

Nigeria does not need definitions that absolve killers. Nigeria does not need ecclesiastical interpretations of genocide. Nigeria doesn’t need Kukah’s theology of convenience. Nigeria needs truth. Nigeria needs courage. Nigeria needs religious leaders who speak to sufferings, not around them. The women whose husbands were murdered need a voice. The children who saw their schools torched need witnesses. The communities forced to flee their lands need validation. They do not need a lecture on intent.

If genocide is only what one proves in court, then the crime has already won. If suffering must be verified by the Vatican memo, then the dead are silenced twice. If terror requires sanction from hierarchy, then the victims remain irrelevant. This is the dangerous gift of reductionism. It allows moral authority to be divorced from moral courage. It allows words to mask horror. It allows convenience to masquerade as wisdom. Bishop Kukah should remember Romero. He should remember Freire. He should remember priests who risked their lives and comfort to defend the defenseless. The world remembers their courage. The world remembers their solidarity. The world does not remember bureaucratic definitions that sanitise violence. The world does not remember numbers when names are forgotten. The world remembers those who speak for the voiceless, not those who repackage terror as a matter of semantics.

In Nigeria today, churches are burnt. Villages are attacked. Lives are lost. Families are destroyed. Fear spreads. And yet, what we hear from Bishop Kukah is that genocide cannot be named. We hear that intent alone matters. We hear that numbers without Vatican verification are hearsay. His words are a monument to reductionism. His words are a guide for those who would obscure horror. His words betray the moral responsibility of religious leadership when faith demands more, demands courage, demands naming the suffering and demands standing with the victims even when power pressures one to be cautious. Faith is not a tool to sanitise terror. It is a sword against oppression. And that is what Kukah seems to have forgotten.

Bishop Kukah once poked the eyes of oppressors. Today, he seems to shield them. He once championed truth. Today, he sanitises horror. He once had the voice of the oppressed. Today, he theologises convenience. History will judge him. History will remember the voices he ignored. History will remember that genocide is more than intent. History will remember those who spoke for the dead while the living waited for validation from men in suits and pulpits. Nigeria needs more than definitions. It needs courage. It needs truth. It needs religious leaders unafraid to name horror and challenge impunity. Bishop Kukah has chosen another path. He has chosen the path of convenience and of reduction. And that is the tragedy of his moral retreat.

Unfortunately, the retreat is what his New Theology of Convenience is about.

***Abdul Mahmud is the President of the Public Interest Lawyers League (PILL).